CC BY ND Jochen A.G. Jaeger, Ariel Spanowicz and Fernanda Zimmermann Teixeira

透過分析找出最適當的防護圍籬架設方式,有助於改善和減緩動物路殺

許多動物因為要尋找水源、食物、躲藏度冬地點、巢位或是配偶,不得不頻繁穿越道路。隨著各國經濟開發,路網越來越複雜,行駛路上的車輛也越來越多,導致動物路殺事件與日劇增。

根據葡萄牙籍道路生態學者Grilo(曾於兩年前來過台灣)等人2020最新研究,歐洲每年因為路殺死亡的鳥類高達1億9千4百萬隻,哺乳類則約有2千9百萬隻,Grilo等學者以數學模型分析的結果也顯示一件重要事情,路殺數量最多的物種,不一定就是受到路殺威脅最嚴重的物種,必需要同時考慮道路對整個物種族群的長期影響才能評斷之,唯有如此才不會將有限資源投注在錯誤的目標物種。

最常用來改善和減緩動物路殺的方式是動物防護圍籬,但安裝和維護防護圍籬是昂貴的(許多國家的防護圍籬規模通常是幾十公里的長度),因此除非動物路殺真的對用路人的交通安全構成很大威脅,否則交通部門通常會忽略動物路殺而不願處理。

動物防護圍籬的建構雖然可以減少路殺的發生,卻也對動物的移動造成障礙,是兩面刃!將整個道路兩側圍起來,是不切實際的。因此防護圍籬該架在那裡?長度又該是多少?就成為很重要的研究課題!!

(高速公路局於國道3號設立的動物防護圍籬,主要目標物種為石虎和白鼻心等移動能力較強的物種,因此圍籬長度經常超過1500公尺)

(高速公路局於國道3號設立的動物防護圍籬,主要目標物種為石虎和白鼻心等移動能力較強的物種,因此圍籬長度經常超過1500公尺)

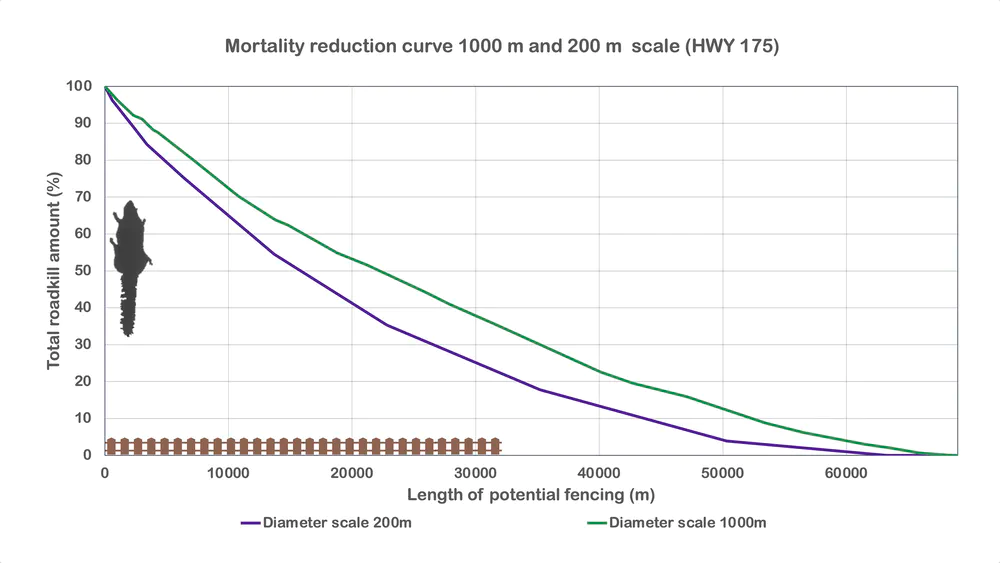

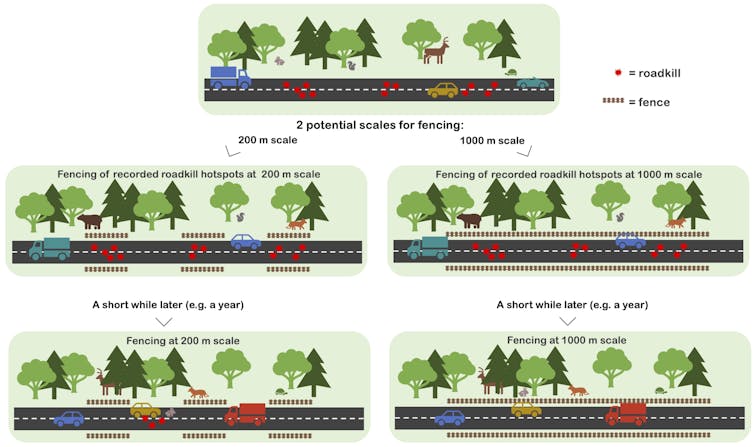

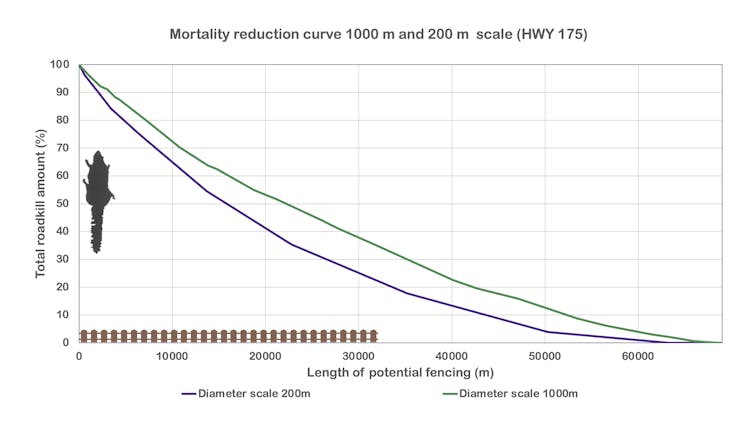

研究學者以巴西交通部門的動物路殺資料做基礎,用不同尺度(長度)規模分析路殺熱點,因為分析尺度的不同,所得到的熱點常常也會有所不同,在某個尺度下是路殺熱點,但放到另一個尺度下可能就不是熱點,這也將影響防護圍籬該如何架設的決策,因此透過這樣不同尺度的方式分析比較,找出最適當的方式,就有其必要性!

(路殺社建議公路總局於北橫公路58至59公里間,設立供蛇類和蛙類攀爬離開路面的菱形網,就是採用本文間隔設立防護圍籬的概念)

(路殺社建議公路總局於北橫公路58至59公里間,設立供蛇類和蛙類攀爬離開路面的菱形網,就是採用本文間隔設立防護圍籬的概念)

學者的假設是:在一個動物路殺熱點路段,以間隔方式設立多道短防護圍籬,其改善和減緩路殺的成效,在沒有「圍籬末端效應fence-end effect」*時,可以和整段路都圍起來的效果一樣!若真是如此,將可降低圍籬架設的總長度,減少總成本支出。

「圍籬末端效應fence-end effect」是指:當防護圍籬太短時,動物可以輕易的沿著圍籬走並從圍籬末端的缺口進入道路,因此而被路殺死亡。所以圍籬必需要足夠長以降低圍籬末端效應的影響。Animals can move easily around fences that are too short. They may then get killed at the fence ends — an issue known as the “fence-end effect.” The fences need to be long enough to reduce the danger of a fence-end effect.

單一長圍籬較好?還是多道間隔架設的短圍籬比較能減緩路殺?

單一長防護圍籬或是間隔架設多道短防護圍籬較能有效減緩動物路殺,在生態保育上有其重要性!如何找出這個平衡點,建構合適的防護圍籬和動物的移動能力以及面對防護圍籬時的行為有關,也會受到熱點路段的地景條件有關,舉例來說,斑龜的移動能力較石虎差很多,其路殺熱點也會較為集中,因此多道短圍籬的方式架設,較有利減緩斑龜的路殺,但石虎則需要較長的防護圍籬,以避免石虎沿著防護圍籬走並從末端缺口進入道路。簡單說就是:防護圍籬的架設要因地制宜、因物種而不同。

還有一點很重要的觀念,隨著防護圍籬的架設,原本的動物路殺熱點可能因此獲得改善而消失,但也可能發生轉移並出現新的熱點,因此路殺減緩設施一定要做成效監控並適時的調整。

研究學者在巴西三條道路上的動物路殺熱點建構了不同長度的動物防護圍籬,後續的研究成果顯示,隨著動物防護圍籬的架設,能有效降低路殺的發生,同時也能提高用路人(汽機車駕駛)的安全性,是一個已被証實有效且具有彈性的方式。整體而言,在沒有「圍籬末端效應」的情形下,架設多道短防護圍籬的方式,可以降低建構和維護成本,而且對於路殺減緩改善的成效甚至優於單一或較少的長防護圍籬。

詳細細節請見下方原文

Wildlife can be saved from becoming roadkill with a new tool that finds the best locations for fences

Jochen A.G. Jaeger, Concordia University; Ariel Spanowicz, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, and Fernanda Zimmermann Teixeira, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul

Wild animals move through landscapes to find water, food, shelter, mates and nesting sites, but roads and traffic make it more difficult and dangerous for them. As many countries move to expand their road networks, especially in tropical areas, an increasing number of mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians face the risk of being killed.

Roads and traffic already kill a massive amount of wildlife, which can lead to the loss of local populations, including species that live in low densities or reproduce slowly, like lynx, badgers, porcupines, turtles and owls. This can have cascading effects — interrupting mutually beneficial relationships or rupturing food webs — that can lead to the loss of other species.

Depending on the country, roadkill can range from hundreds of thousands to several hundred million animals annually. According to a recent study, an estimated 194 million birds and 29 million mammals are killed each year on European roads. Some jurisdictions have taken measures to reduce roadkill — the Netherlands and Switzerland, for example, have wildlife fences and passages — but it still is an increasing global concern.

Wildlife fences, installed along the length of the road, reduce wildlife mortality, but they can be controversial. They are often considered unpleasant compared to “cool” wildlife overpasses, because they add to the barrier effect caused by roads in the first place.

We devised a plan for prioritizing roads sections for wildlife fencing to reduce roadkill, based on the identification of roadkill hot spots and cold spots.

Essential, but controversial

It is expensive to install and maintain fencing to prevent animals from dying in traffic. Unless it is relevant to driver safety, transportation agencies have largely neglected to reduce roadkill.

When transportation agencies and wildlife managers are asked about their thoughts on installing fences along roads, many are skeptical and often view them as unpleasant features. In contrast, wildlife overpasses are viewed as “cool.” In reality, however, those “cool bridges” alone do not reduce road mortality.

Recent evidence indicates that road mortality is more detrimental to most wildlife populations than fences. In the majority of cases, fences are more urgently required than wildlife passages. But how long should they be and where is the need most pressing?

Roadkill hot spots

Fencing entire road networks is not realistic. We determined how transportation agencies might prioritize road sections for fencing by using mortality surveys, identifying roadkill hot spots at multiple scales and planning mitigation measures in a methodical way that follows an adaptive-management approach.

Roadkill hot spots can be identified at different scales, which can influence decisions about where fences should be placed. A hot spot at one scale may not be a hot spot at another scale.

We used roadkill data from three roads, one from southern Québec and two from Rio Grande do Sul, in Brazil. The first road cuts through the Laurentides Wildlife Reserve and borders the Jacques-Cartier National Park in Québec. One of the roads in Brazil crosses through two protected areas and runs along the Atlantic Forest Biosphere Reserve, while the other borders slopes of the Serra Geral Mountains and coastal lagoons.

Initially, we thought many sections of short fences could be built near hot spots identified at a fine scale to reduce roadkill. We expected that this approach might also require less total fence length than fencing fewer hot spots identified at courser scales while achieving the same roadkill reduction.

However, animals can move easily around fences that are too short. They may then get killed at the fence ends — an issue known as the “fence-end effect.” The fences need to be long enough to reduce the danger of a fence-end effect.

A few long fences or many short ones?

This trade-off between the use of a few long or many short fences has important implications for biodiversity conservation. Finding the right balance depends on the distances that animals move, their behaviour at the fence, the mortality reduction targets for each species considered and the structure of the landscape near the road.

For example, turtles move across much shorter distances than lynx, and their roadkill hot spots are very localized. Accordingly, many short fences are appropriate for turtles, whereas fences designed for lynx need to be much longer.

After fences have been installed, roadkill hot spots can disappear or shift, and new ones may appear, so road mitigation must be able to adapt. Our step-by-step plan helps transportation managers decide where to place fences, and whether they should be long or short.

Fencing has been shown to be effective and is the most realistic way to decrease roadkill. Wildlife conservationists and transportation agencies should install fences more actively than wildlife passages to reduce the effect of roads and traffic on wildlife populations. Fences also increase traffic safety for drivers.

Thus, given the global boom in road construction on the planet, biodiversity is under rapidly increasing threat and the need to reduce road mortality globally, and to add wildlife fences, is more urgent than ever.![]()

Jochen A.G. Jaeger, Associate Professor, Geography, Planning and Environment, Concordia University; Ariel Spanowicz, MSc student in Environmental Science, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, and Fernanda Zimmermann Teixeira, Postdoctoral researcher, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.